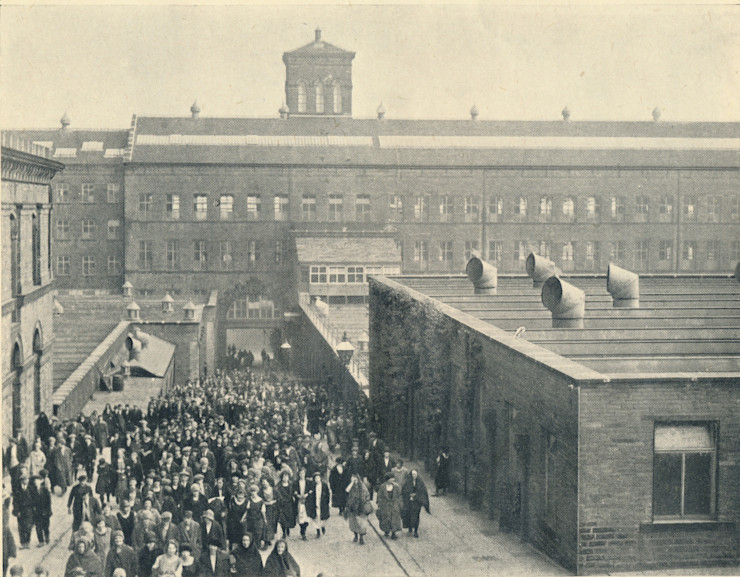

Gary Firth's book Bradford and the Industrial Revolution takes its reader on a journey through time from a relatively settled rural scene to a town bustling with industry. I draw on this book and other sources for this post. The image is of the Black Dyke Mill with thank to the music venue it now is.

We begin with the geology of Bradfordale noting the different areas and soil types, essentially coal measures and millstone grit. These soils, taken with the wet climate, made the area unsuitable for much arable farming and not particularly productive for livestock which tended to be mainly milking cows with some poor beef cattle and sheep producing fleeces far smaller than breeds in the more productive east of England. The net result was small holdings supplementing their income with spinning and weaving of wool into worsted cloth.

Firth suggests that change came about with growing demand for food from the slowly expanding urban population of Bradford then little more that a large village. The demand for food could not be met from elsewhere given poor communications and so the challenge rested with the local tenant farmers and landlords. The process, if it can be called that, was for the steady improvement of neglected land by means of manure and lime and better husbandry. Farms increased in size and now focused on food production. Spinners and weavers gravitated to Bradford increasing further the hungry urban population. In time they were joined by spinners and weavers from elsewhere in the country with the urban population increasing by a massive 1,064 % between 1780 and 1850 to 52,493. West Yorkshire had overtaken both Norfolk and the West Country in worsted production.

The availability of raw materials was, as elsewhere, fundamental to further development. There was coal, this being the north western end of the Yorkshire coalfield. There was iron ore and limestone. Firth writes of the many kilns burning lime both for agricultural use and to make lime mortar for building. The Low Moor iron works burst into action with the introduction of blowing pumps using Boulton & Watts steam engines. These enabled blast furnaces which could use the vast coal reserves to produce iron in substantial quantities just when it was needed for armaments for the wars against Napoleon. For the next decades the iron works developed continually, taking on technical improvements as they became available. Other iron works developed alongside including the Bowling Iron works which was famed for its wrought iron boiler plate. It sent on to produce steel using Siemens Martin furnaces. Bradford became one of the most significant producers in Yorkshire.

An essential element was the availability of finance and I write about this in this blog. Bradford was similar to other places where the volume of production and trade was growing with merchants branching out into banking. Firth offers many examples of finance provided including for the Low Moor Iron Works and a number of mills including the Black Dyke.

Without better communications linking Bradford to its markets growth would be restricted and so the digging of the canals was once again key. The Aire-Calder navigation provided the link to the east coast and to markets in Holland and Germany. For the west, Firth suggests that it was the Bradford colliery owners who provided the impetus for the digging of the Leeds-Liverpool canal; the link to Bradford itself was added later. Whilst the Yorkshire collieries certainly benefitted from the Leeds-Liverpool canal, so to did those in Lancashire and it added greatly to the prosperity of the whole area.

The making of worsted cloth first became factory based in 1786 with Cockshott & Lister using water power. Steam power came in first at the Tong Park Mill using a steam engine provided by Boulton & Watt. Other mills followed but it took more than a decade for the advantages of the factory system to become evident. Ramsbottom and Murgatroyd introduced steam power into their mill at Holme in 1800.

At that time Bradford and Halifax were pretty well neck and neck but over the next couple of decades Bradford took the lead in plain worsted cloth leaving Halifax with the more 'fancy' cloths. Wool came via the market in Wakefield from Lincolnshire, Leicestershire, Kent and the Cotswolds. Customers were in the south American colonies but more importantly Germany. A strike by weavers in 1825 convinced mill owners of the need to mechanise and more and more steam driven machinery was brought into the mills. Wool consumption had risen to 6 million lbs a year by 1825. Now the clear leader in worsted production, Bradford attracted dyers but also merchants and by 1851 was the Capital of the worsted trade. I write in my blog on that city how worsted production gravitated from Leeds to Bradford leaving Leeds to focus on the making of clothing.

Samuel Lister was highly influential in Bradford textiles. He was at heart an inventor and his nib comb was said to have revolutionised the worsted industry. He branched out into other textiles and his Manningham Mill was at one time the largest silk factory in the world employing 11,000 people. Titus Salt was another famous Bradford mill owner but his fame came from leaving the crowded town and setting up a revolutionary new mill at nearby Saltaire (named after Salt). Not only was the mill state of the art but 'housing was provided of the highest quality. Each had a water supply, gas lighting, an outdoor privy, separate living and cooking spaces and several bedrooms. This compared favourably with the typical worker's cottage'.

The infrastructure of Bradford improved over the succeeding decades. Two railways made their way into the town. The Midland Railway provided access north and south. A line from from Halifax via Low Moor was opened by the Leeds & Yorkshire railway and the GNR ran a line from Leeds into Bradford. Telegraph and in time telephone then appeared with the town's fathers expressing anxiety at the wires trailing from street to street. Anxieties were addressed and a General Post Office was built. Electricity then beckoned, but, like many English towns gas had got there first and investors were reluctant to let electricity siphon off their profits. Transport within the town was an issue and the fashion for trams running on rails won the argument, but not powered by electricity; it was to be steam for Bradford. In time electricity did come into the streets and homes and to power the trams.

In terms of industry, Low Moor prospered up until the First World War when it experienced a brief surge in demand. Thereafter the story was one of decline. The worsted trade prospered for rather longer but succumbed to the pressure of cheap imports and lower wages overseas. The motor industry made its mark in Bradford with the establishment of Jowett Cars in 1906. This company went on to produced much-loved up-market cars, the Javelin and Jupiter.

Bradford is currently enjoying an economic resurgence along with neighbouring Leeds.

Further reading:

Gary Firth, Bradford and the Industrial Revolution (Halifax: Ryburn Publishing, 1990)

www.bradfordmuseums.org

No comments:

Post a Comment