Crewe is the third town cited by Asa Briggs as created in the 19th century. It was created by the railways for the railways and Diane Drummond, in her book Crewe: Railway Town , Company and People 1840-1914, offers a precise date, 10 March 1843, when the first employees and their families were settled there.

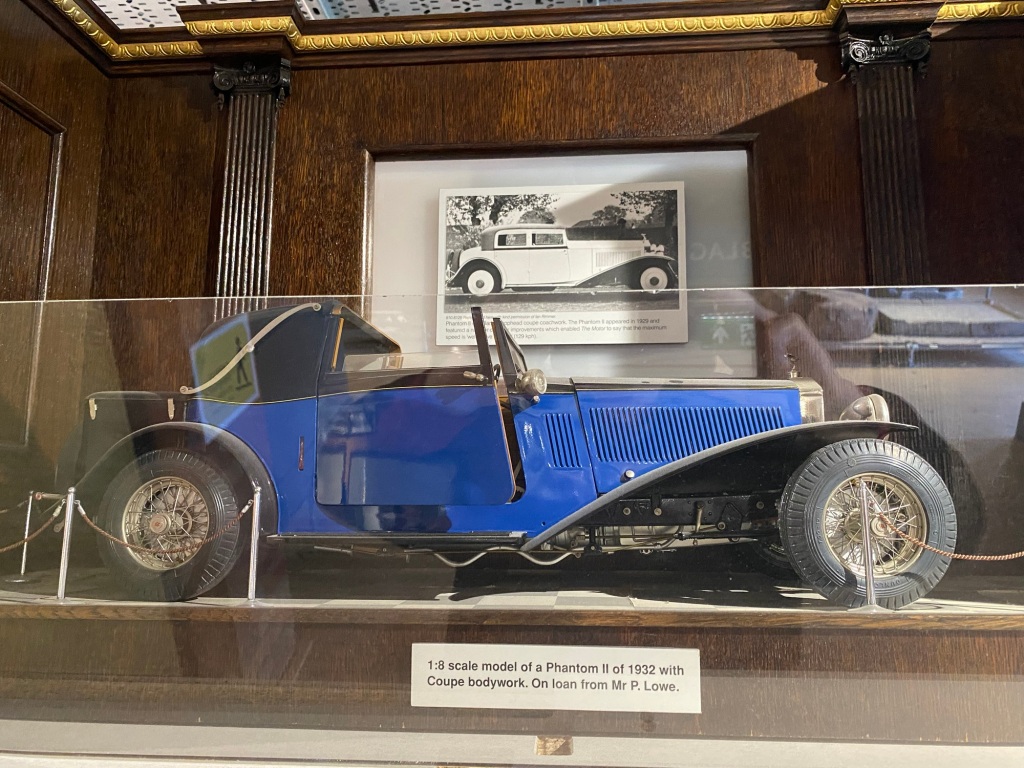

It later became home to Rolls-Royce Motors. The image is of General Montgomery's Rolls-Royce probably manufactured in Derby (see below).

It was the Grand Junction Railway that decided Crewe was the place for its main works. It had become the place where a number of separate railway lines met what would become the west coast mainline and so it was a logical location for the factory that would maintain and manufacture locomotives and rolling stock but also rails.

Drummond offers a glimpse of the scale of railway manufacture by comparing Crewe with Swindon which was home to the works of the Great Western Railway. Crewe's initial workforce in 1843 numbered 1,150 compared to Swindon's 423. However by 1847 as a result of economic downturn, Crewe's workforce had reduced to 1,000 whereas Swindon's had increased to 1,800. Looking further ahead to 1900, Crewe employed 7,500 and Swindon 11,500.

Crewe might not have been the biggest, but it laid claim to be the most technologically advanced. Drummond suggests that, having a single customer, the works followed a path of vertical integration. At one time it made everything used in locomotive manufacture except copper piping. Famously it built its own iron and steel works being one of the first to embrace the Bessemer and then the Siemens-Martin processes. Carr and Taplin, in their History of the British Steel Industry, tell how the Chief Mechanical Engineer, John Ramsbottom was persuaded by William Siemens to instal open hearth furnaces for the conversion of old iron into new steel rails. In addition to furnaces, Ramsbotton installed a new rail-rolling mill to be added to ten years later by a second mill with an updated design by the next Chief Mechanical Engineer, Francis Webb. These two respected engineers followed in the footsteps of Francis Trevethick, son of Richard Trevethick, who set up the Crewe works.

It was said that Crewe built locomotives for economy, leaving GWR to win plaudits for power and speed. Nevertheless, Crewe earned respect for their training of young engineers among whom was Nigel Gresley. From the start, Crewe operated a division of labour with as many as nineteen different trades including: 'smiths and their strikers; moulders and their assistant dressers and casters; pattern makers and coppersmiths; boilermaking trades of platers, riveters and 'holders-up'; turners; coachbuilders and engine fitters'. Basic machine tools were employed such as lathes, 'slotting, shaping and planing machines'. Under Ramsbottom new machine tools were introduced in the 1860s and 1870s resulting in increasing standardisation using interchangeable parts. In this Crewe was perhaps twenty years ahead of the so called Machine Tool Revolution which transformed other engineering companies in the 1890s. One consequence of the increase in mechanisation was a change in the composition of the workforce with a higher proportion of general labourers and fewer skilled men.

Drummond takes her reader through the essential elements of the process of constructing a railway locomotive which I simplify in the interests of highlighting the growing role of machine tools. The starting point is the foundry where the iron is made which can then be cast, or puddled to become more malleable wrought iron. The invention of steel eventually took the place of wrought iron. In the railway workshop, parts would first be moulded, that is a mould would be created and the molten metal introduced. Moulds varied massively in complexity and so the skill required in their making. Should parts need to be joined, this was then undertaken by the smithy. Welding, as we know it, came very much later. A locomotive could comprise some 5,000 parts each of which would require a degree of finishing using perhaps a lathe. This was the job of the turner. As time progressed the number of machine tools increased and so a larger proportion of the work was carried out by semi-skilled machinists. For a locomotive, the construction of the boiler was central. Again, this was a combination of skill, machine power and stamina - it was hard work. The final part of the process was down to teams of fitter-erectors who would put all the parts together; this was one of the last stages of the process to employ machine tools. (I can't help having in my minds eye, as a contrast, the robots on the production line at today's Derby works)

This was surely a complex process and one that had to be married with work in repairing locomotives. The whole was carried out in a cyclical economy presenting management with massive challenges in balancing the books. At Crewe a device of compulsory unpaid holiday was used to match the workforce with the hours needed for the work. This unsatisfactory arrangement was eventually superseded by lay-offs, inevitably met with resistance.

All this happened in a town where employment in the railway works was life for a large proportion of the population. Towns with a wider spread of employment were far less vulnerable to the foibles of the economy.

For Crewe, the years immediately preceding the Second World War brought Rolls-Royce and a factory to manufacture aero engines. (The image is of General Montgomery's Rolls-Royce probably made in the Derby factory.) After the war the factory took over the manufacture of both Rolls-Royce and Bentley motor cars, with the Derby factory giving its focus to jet aero engines. As I tell in Vehicles to Vaccines, Rolls-Royce Motors split off from the aero-engine company and continued manufacturing in Crewe. At the turn of the twentieth century the German BMW bought Rolls-Royce and built a new factory at Goodwood in Sussex, VW took the Bentley brand and upgraded the Crewe factory. Both companies continue to trade successfully under their new ownership. Bentley is now the largest private sector employer in Crewe.

Further reading:

- J.C. Carr and W. Taplin, History of the British Steel Industry, (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1962)

- Diane K. Drummond, Crewe: Railway Town, Company and People 1840-1914 (Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1995)

.jpg)