In many ways Manchester was the home of the Industrial Revolution. The mass production of cotton fabrics began there and its was this thatdrove the British economy. I tell much more on my book How Britain Shaped the Manufacturing World (HBSTMW) . Much more was to come as I tell below

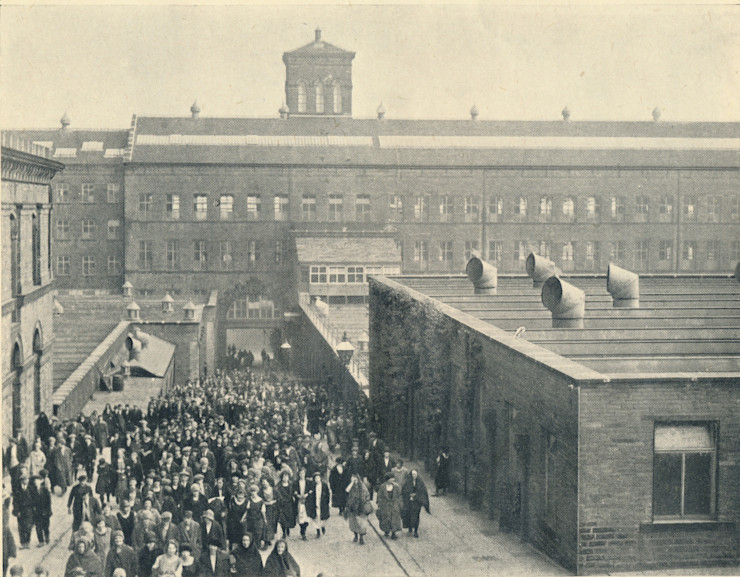

The eighteenth century saw Manchester textile merchants grow their networks of outworkers to spin and weave the cotton that was being imported in ever increasing quantities. In time a factory system emerged with incremental steps of mechanisation and I describe these in the chapter on textiles in HBSTMW. Cotton mills were visible throughout Lancashire. The Museum of Science and Industry tells much of Manchester's story. The early part was all about textiles, but then the machinery that made textiles and the other machinery that served this world.

Opinions differ on the both the significance and date of the introduction of machinery into the cotton industry and in particular the factory system. Roger Lloyd-Jones and M.J. Lewis, who also wrote the book on Alfred Herbert which shed so much light on British machine tools, explored these questions in Manchester and the Age of the Factory. Their methodology is interesting. We are talking of a period before the census and so the first question was just how to measure the relative importance of factories compared to the warehouses that stored and distributed the production of our workers. They chose rateable values taken from the Manchester Poor Rate Assessment Books which attribute to properties a market value which the authors argue reflect economic activity. I won't go into the reasoning offered in support of this but rather refer readers to their book. I will, however draw upon their findings.

In looking at the properties in Manchester categorised as factories or warehouses and used in the cotton trade, the authors found firstly very few large businesses occupying whole buildings. Rather, the trade was fragmented with multiple occupation of both warehouses and factories. Looking at the factories, many were small workshops spinning yarn using the recently invented machinery. Weaving looms were predominantly hand operated since the early iterations of mechanisation were by their nature experimental. Manchester warehouses would act as merchants for yarn supplying the hand weavers and taking the finished product for onward sale. Spinners and weavers alike could be in the city or elsewhere in Lancashire.

To me this sounded like a sensible division of labour in an integrated process. Not so the reality of business in Manchester before and during the Napoleonic wars. The evidence is of a schism with the spinner selling their yarn to continental weavers. The Lancashire weavers suffered with unemployment the result. In HBSTMW I referred to the unrest and its expression in the Peterloo massacre. These were hard times.

In the aftermath of war and after much argument, the overall good of Lancashire business prevailed not least as looms became steam powered under a factory system. One line of argument was that factory based spinning was exploiting child labour just as the country was becoming aware of the damage caused by unregulated factories. In HBSTMW I noted that competition had driven down prices putting pressure on weavers to mechanise.

Looking at some of the mills, one of the biggest was owned by McConnel and Kennedy. They were spinners but later classified also as doublers. Tracing their story forward in time, they become McConnel and Co and then in 1898 were bought by the Fine Cotton Spinners and Doublers Association. This can then be traced through to Courtaulds, which, as I tell in Vehicles to Vaccines, brought together a large number of mills to secure the market for their man-made fibres.

Another mill developed into an integrated cotton manufacturer, Tootal Broadhust Lee, which carried out spinning and weaving under the same roof. The name Tootal readers may recall in the context of men's shirts. The company became part of Coates Viyella in 1991.

Mechanisation began in the factory or workplace often by the spinner or weaver making his own quite basic machinery. Larger entities could employ engineers both to maintain machinery and develop and make new. At some point between 1815 and 1825 the demand for machinery became such that separate machine making businesses set up to serve the market of spinners and weavers. Lloyd-Jones and Lewis write of such establishments being located beside the Ashton and Rochdale canals. Business names are mentioned: Peel and Williams (the subject of a chapter in the book 'Science & Technology in the Industrial Revolution' by A. E. Musson and Eric Robinson), Ebeneezer Smith, Hewes and Rwen, Richard Ormerods, Radford and Waddington, Galloway and Company and the Fairburn Engineering Company. William Fairburn also built some of the early steamships.

Lloyd-Jones and Lewis add to the metal workers, Dyers and Printers and describe all three as the 'modern sector'. We are talking about the developments in bleaching with the use of chlorine, but also the experimentation with different dyes. These then combine with the metal workers when we bring in cylinder printing machines powered by steam. In terms of production, spinners, weavers, dyers and printers sometimes combined in single businesses. Thomas Hoyle is an example of integrated dyeing and printing. The company became part of the Calico Printers Association, which employed the inventors of terylene which ICI then developed, and which later became part of Tootal. Nonetheless a good part of the business remained in small units.

Manchester had become a modern industrial economy and other developments followed.

In the nineteenth century Joseph Whitworth (located opposite Richard Ormerod) was manufacturing screws following his own design. His company expanded into arms production and as such was a rival to Armstrongs in Newcastle. The matter was settled by a merger followed in due course by a further merger with Vickers. The works at Openshaw became part of the English Steel Corporation owned by Vickers and Cammell; it was brought into British Steel on nationalisation.

Trafford Park in Manchester, built by the notorious entrepreneur ET Hooley, in 1897 became home to British Westinghouse. I write of them in my blog on the American Electricity Industry. The British market was becoming attractive and Westinghouse set out to compete with his fierce rivals British Thomson Houston and Thomas Edison who had combined in General Electric and set up in Rugby. In Manchester, British Westinghouse later became part of Metropolitan Vickers by series of financial moves which I describe in HBSTMW. It then joined with its fierce rival as part of AEI and in turn became part of GEC which had a significant presence in the city: GEC Turbine Generators and Switchgear and GEC Traction.

Trafford Park was also home to Ford UK, before the latter moved to Dagenham, and part of the Dyestuffs division of ICI which first manufactured Penicillin. Courtaulds had a chemical works on Trafford Park.

Withenshaw to the south of Great Manchester was home to the AEI (later GEC) transformer factory. AV Roe began building aircraft in Brownfield Mill and later moved to Newton Heath where Mather & Platt's vast works produced pumps and electrical machinery.

In the Second World War, Patricroft Royal Ordnance factory was built on the site of the former Naysmith Engineering Works, originally established in 1834, by the Bridgewater Canal in Eccles on the outskirts of Manchester. Employing 3,000 people, it specialised in welding and fabrication, also making parts for Bofors guns. As a precursor to the city's role in alloys and new materials, a shadow factory run by Magnesium Elektron (now part of Luxfor Group plc and still manufacturing in Manchester) produced magnesium alloys.

The city was home to one of the early computers manufactured by Ferranti in conjunction with Manchester University. You can discover more at the Museum of Science and Industry. I tell more about the evolution of the British computer industry in Vehicles to Vaccines.

Ferranti had a significant presence. In Hollinwood they made electricity meters and at Chadderton power transformers and testing equipment and also semiconductors and opto-electronics. Moston was where they made instruments, aircraft equipment and fuzes. Process control computers were made at Withenshaw and simulator, sonar and civil computer systems at Cheadle Heath. Computer systems and (post 1975) the company HQ were at Gatley. I am grateful to John F. Wilson for including this detail in his Ferranti A History. The images are of some of the early computers on display. Many of Ferranti’s buildings became part of ICL - some of their products are shown below and are on display at the museum.

Manchester is a city that does not stand still. One successful piece of exploration was graphene, and the Museum of Science and Industry describes how this thinnest possible material was ‘first isolated by scientists at the University of Manchester in 2004 using ordinary sticky tape’. The scientists involved, Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov, were later awarded a Nobel Prize for their work. In his paper on nano materials, Robin McIntyre from PERA sets graphene alongside other carbon-based nano materials, and other such non carbon-based materials nano titanium dioxide and nano-ceramics. These materials are already being used to enhance properties of more common materials such a concrete which graphene strengthens allowing smaller quantities to be used. I also refer to graphene as a material for use in semiconductors. Their potential uses are manifold.

.jpg)