I write of the motor industry in How Britain Shaped the Manufacturing World (HBSTMW) and in three chapters of Vehicles to Vaccines: Volume Car Makers, Speciality Car Makers and Commercial Vehicles and Motor Component Manufacturers. The image is of the Geneva Motor Show in 1949 where the Rootes Group, one of Coventry's finest, are seriously engaged in the post war export drive.

The city of Coventry, long associated with the story of Lady Godiva, had as its major industry the making of ribbons. This trade it shared with neighbouring Nuneaton, Bedworth and much of north Warwickshire. The trade prospered until 1860 and the passing of a law which allowed imports; thereafter Coventry and its neighbours found themselves undercut except for woven tapes. J & J Cash remains in Coventry as manufacturers of name tapes amongst much else.

The other Coventry industry, a child of the industrial revolution when time became relevant to people’s lives, was the making of clocks and watches. The city wasn’t alone in this but it was significant. Nearby Lutterworth was home to the Corrall family who started making clocks in 1727.

Kenneth Richardson in his book Twentieth Century Coventry writes of how in the nineteenth century ‘watchmaking was beginning to supplant [the ribbon trade] in the affections of young men who wished to acquire a skill’. From this grew many small workshops, working in much the same way as their counterparts in London’s Clerkenwell, but also factories such as Rotherhams and the Coventry Movement Company. The industry largely died with the impact of Swiss competition but it did equip the city with skills it would need for its push into vehicles of all kinds. In How Britain Shaped the Manufacturing World I suggest that the skills employed in making sewing machines also translated into the industry of bicycle making.

Richardson does take one important step back by bringing onto centre stage Alfred Herbert. I write in Vehicles to Vaccines of the fundamental importance to manufacturing industry of machine tools. Herbert, the son of a builder, began in 1887 in general engineering but he gravitated toward machine tools and in 1914 was employing 2,000 men making him the largest machine tool maker in England. In time Coventry attracted other machine tool makers including Charles Churchill who brough American machine tool practice from his native USA. Another American, Oscar Hamer, joined Herbert as his general manager. Alfred Herbert subsequently moved to larger premises in Lutterworth. It was taken over by the TI Group. I write more of the machine tools industry in Vehicles to Vaccines.

The manufacture of bicycles in numbers sufficient to supply the market required these machine tools but also entrepreneurs.

The Coventry Riley family had been a ribbon manufacturers but turned their hands to bicycles. From Sussex came the Starleys and George Singer. William Herbert, Alfred’s brother, joined Londoner William Hillman. Thomas Humber came from Beeston just outside Nottingham and Daniel Ridge came over from Wolverhampton. I write about the development of the bicycle industry in How Britain Shaped the Manufacturing World.

The First World War, with its insatiable demands on industry about which I wrote in Ordnance, provided a major boost to Coventry as a growing city of manufacturers. Motor cycles and motor cars followed the bicycle and the city also attracted Courtaulds for the manufacture of Rayon, and telephone and other electronics including British Thomson Houston (BTH) from neighbouring Rugby.

Thomson Houston was one of the major American electrical engineers which had merged with the pioneering Thomas Edison in 1892 and became General Electric (GE) I write of them in my blog on the American Electricity Industry. They viewed the British market as attractive and set up in 1900 to compete with their major rival Westinghouse which had set up in Trafford Park in Manchester in 1897. The Rugby site concentrated on the manufacture of incandescent light bulbs but to this was added heavy electrical engineering as more and more areas of the UK sought electrical generation.

In 1915 GEC bought the Copeswood estate at Stoke in Coventry to build a new factory. Six years later it moved its Peel-Conner telephone manufacturing operations from Manchester to the site, a move that coincided with the BPO (Post Office) standardising their accepted telephone designs. Over the years the company expanded, taking over a number of former Coventry factories producing a large proportion of the Strowger telephone system for the UK. By 1970 GEC, which had combined with AEI and English Electric, had seven factories in the city employing 30,000 people. Its production of the Strowger system ceased in Coventry in 1974. I write in Vehicles to Vaccines of the struggle for supremacy in the subsequent electronic telephone systems. GEC Telecommunications in Coventry was a keen contender.

Like so many British cities, Coventry played a major role in equipping the forces in the First World War, so much so that the city council claimed :

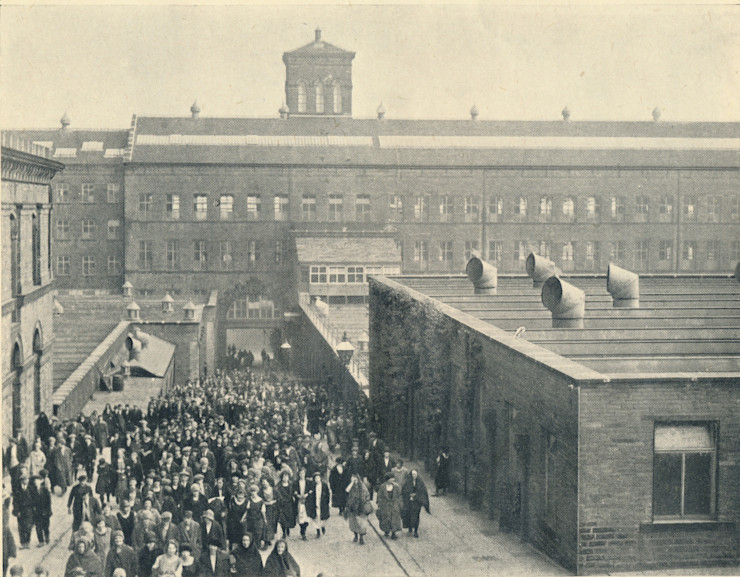

‘It is safe to say that no English city was so completely absorbed in munitions production as Coventry…It was not merely a question of adaptability of existing facilities. New factories sprang up in such numbers and on such a scale as to change the whole face of the city in the matter of a few months. New suburbs grew up like mushrooms, thousands of strangers of both sexes flocked to Coventry from all parts of England in answer to the call for munitions.’

The Coventry Ordnance Factory built beside the Coventry canal manufactured guns so big that machine tools were moved to them rather than the more conventional production line. I write of this in How Britain Shaped the Manufacturing World and my book on army supply in WW1, Ordnance.

Motor car manufacture grew like topsy following the end of the war. By 1931 there were eleven separate motor companies and forty that had tried and failed in the same period. I wrote in How Britain Shaped the Manufacturing World of how Daimler was first but with Lanchester, Siddeley-Deasy close behind. Morris bought the French Hotchkiss. The Rootes brothers combined Humber and Hillman. Vickers had a presence in Coventry through their Wolseley subsidiary later bought by Morris. William Lyons brought the Swallow Sidecar company to the city where it became Jaguar. The Rover company had made bicycles but under the guidance of the Wilkes brothers became producers of luxury cars and, after the Second World War, the Land Rover.

It wasn’t just the main manufacturers, components companies came. Birmingham’s Dunlop bought a wheel and rim manufacturer in the city and added to this its Aviation and Engineering Divisions. White and Poppe made engines and Carbodies was established by a former Daimler employee.

The Second World War presented yet further challenges for the manufacturers of the city. As I argue elsewhere, the war for the manufacturers began in the mid thirties with the building of the shadow factories for aircraft production and I write about this major initiative in How Britain Shaped the Manufacturing World. As well as providing vital capacity for the motor companies to supplement the production of the main aircraft companies, they provided space for the motor companies and others to expand when, after the war, the nation was desperate for exports to pay for imports of food and materials.

Between 1939 and 1945, BTH in Coventry and Leicester provided 500,000 magnetos for the RAF. J.D Siddeley expanded his aircraft production at nearby Bagington. T.G John of Alvis became in effect a subcontractor to Rolls-Royce for the repair of engines. GEC manufactured the VHF radio link for the RAF enabling the Squadron Leader to communicate in flight with all his aircraft. Alfred Herbert manufactured some 65,000 machine tools and Gauge and Tool provided measuring devices for the huge armament industry.

The Second World War also brought a devastating night of enemy bombing on 14 November 1940 which destroyed the greater part of the cathedral and many factories including old cycle factories: the Coventry Machinists’ Works, the Rover Meteor Works and the Triumph factory. I write in War on Wheels how the people of the city rose to the challenge of the disaster.

Aviation came to Coventry with the shadow factories. Armstrong-Whitworth moved their aero business to the old RAF airfield at Whitley a little outside the city where they built a supersonic wind tunnel linked to a Ferranti Pegasus computer. Hawker Siddeley chose the site at Baginton that would become Coventry Airport for their production. Lucas aerospace had a presence in the city. I write of post-war aviation in Vehicles to Vaccines.

Sir Frank Whittle and the invention of the jet engine belongs to Midlands manufacturing towns. One of the two prototype engines was made by BTH at Lutterworth; the other by Metrovick in Manchester. Subsequent development through the company Power Jets was based at Whetstone just south of Leicester. I write of the early development of the jet engine in How Britain Shaped the Manufacturing World.

Coventry thrived with this combination of machine tools, motor cars, aeroplanes, manmade fibres and electronics. For a whole variety of different reasons of which I write in Vehicles to Vaccines, the city’s manufacturing shrunk but did not disappear. Jaguar Land Rover have their corporate office at Whitley, the Manufacturing Technology Centre is based at Ansty Park and Aston Martin Lagonda is at Gaydon.

Further reading

Kenneth Richardson, Twentieth Century Coventry (London: Macmillan, 1972)

Graces Guide

https://www.britishtelephones.com/

.jpg)