Liverpool was primarily a port and so concerned with import and export and activities in support of shipping including some shipbuilding. Other towns on Merseyside (including St Helens, Wides and Runcorn) were more defined by their role in chemical production in support of Lancashire’s textile industry; Liverpool did, though, have soap manufacturers, Hudsons.

Looking at Liverpool manufacturers, the early industries were mainly concerned with processing imports. So, there were sugar refineries eventually coming together as Tate & Lyle. There were flour mills including those of Rank. From these other food producers emerged: biscuits (Crawfords and Jacobs) and jam (Hartleys).

There was some shipbuilding. Cammell of Sheffield later merged with Laird which had begun as the Birkenhead Iron works and became a renowned shipbuilder. Ships were also built for inland water ways. In 1900 steel maker John Summers built a large new works at Hawarden Bridge and by 1920 it was one of Britain’s largest producers of sheet steel. Frank Hornby founded Meccano in the city and this later grew to encompass Dinky model vehicles and Hornby trains. Hornby later moved to Margate in Kent.

Lever Brothers, now part of Unilever, began making soap in Warrington, but then created factories at Port Sunlight and built a village for their employees. I write of its growth in both How Britain Shaped the Manufacturing World and Vehicles to Vaccines. The manufacture of soap and margarine from vegetable fat had the by-product of cattle feed of which the town became a major producer.

The spread of electricity generation and communication by telephone and telegraph reached all the big cities. For Liverpool this had added importance with its global shipping trade. Liverpool saw the formation of Automatic Telephone and Electric Company in 1912. In Prescot, British Insulated Cables produced cables and overhead transmission systems. Much later, but I suspect building in this heritage, Plessey set up the secret Exchange Works at Cheapside for the UK Air Defence System and a telephone factory at Edge Lane. Marconi established their first wireless service depot at Seaforth in 1903. I write more about Marconi and the development of wireless communication first with shipping in How Britain Shaped the Manufacturing World.

Liverpool and Merseyside more generally became the object of governmental intervention quite early on. In the First World War this largely built on the Merseyside chemical industry and included the production of phenol at Ellesmere Port, T.N.T at Litherland and Queen's Ferry, ammunition at St Helens and a National Aircraft Factory at Aintree. In 1931 the Lancashire Industrial Development Corporation focused on support for new industries in Merseyside but also the cotton towns, Wigan and Manchester itself. This was followed in 1936 but a then unique scheme which gave to Liverpool City Council power to acquire land and build factories in the city's outskirts. The power was used initially to create two new industrial estates, one at Speke and the other at Fazakerley (renamed Aintree in 1952). The outbreak of the Second World War delayed the planned development of the estate with instead the creation of Royal Ordnance Factories. After the war, the employment situation once again became acute as did the shortage of housing caused largely by war time bomb damage. The issues were addressed by the large scale movement of people to new towns (Skelmersdale and Runcorn) and over spill areas such as Ellsemere Port.

The Rootes Group ran a shadow factory in Speke in the Second World war which was later taken over by Dunlop adding to the rubber industry in the area. Standard Triumph built a paint, trim and bodyshop. The Ford plant at nearby Halewood was second only to its Dagenham works. British Leyland built a plant at Speke which closed in 1978. Glaxo set up a secondary manufacturing plant there. Those plants designated as secondary took chemicals from their primary plants and formed them into the final medicine adding also the means of administration. Astra-Zeneca manufactures vaccines at Speke.

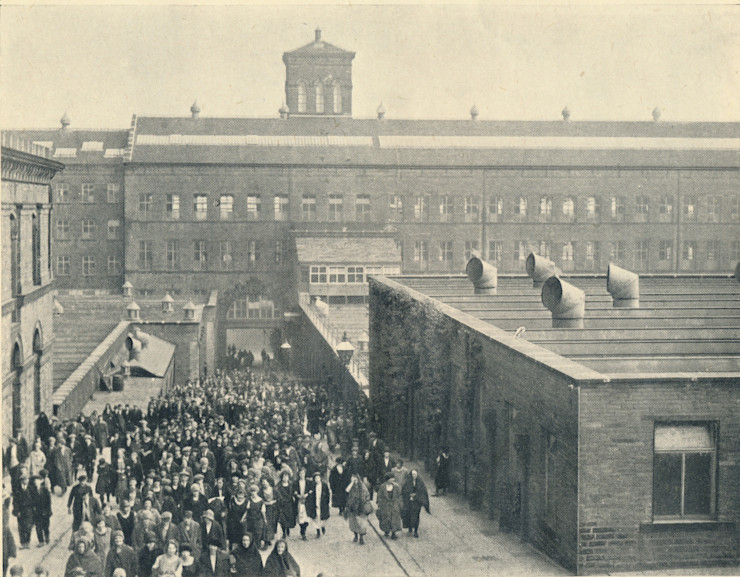

Lucas bought the former Royal Ordnance factory at Fazakerley was had been purpose built, opening in 1941 with a workforce of twelve thousand, 70% of whom were women, and made nearly half of the five million small arms produced during the war. It produced three quarters of a million No 4 rifles which replaced the Lee-Enfield. Courtaulds had a plant at Aintree producing artificial silk. English Electric had taken over the D. Napier & Sons aero engine factory and added a further large factory to produce a range of electrical goods. Schweppes added to their long term presence in Liverpool by building a large factory for minerals and cordials.

Kirby was the site of another Royal Ordnance Factory in the Second World War located there with a view to becoming the core of further industrial development after the war. Parkinson Cowan located a subsidiary, Fisher Bendix, in Kirby. The company was bought by Thorn in the hope of producing gas appliances for the onrush of north sea gas. In the event and despite the efforts of government, industrial unrest resulted in the closure of the plant.

Bromborough had an industrial alcohol distillery run by the Distillers Company. It was also a home to some boat building. The Bromborough Port Industrial Estate was run and largely occupied by Unilever. Girling produced brakes and other motor components there.

Liverpool manufacturing in the twenty-first century includes automotive and aerospace, food and beverage and pharmaceuticals.

Further reading:

Sheila Marriner, The Economic and Social Development of Merseyside

.jpg)